Suppression of Child Malnutrition Survey Data to Shield Gujarat

15/07/2015

Mired by controversies and scandals, the NDA Government has now secured another rare achievement. Recent disclosures, first reported in the ‘Economist’ magazine, indicate that the government has taken great pains to suppress a survey on child health, conducted by the UNICEF, in collaboration with the Government of India. The Rapid Survey on Children (RSOC) was commissioned by the UPA Government and covers the period between 2013 and 2014.

Normally the survey data should have been seen as an important tool for decision making, given that this was the first nationwide survey on child nutrition conducted in almost a decade. The last source of data on child nutrition has been the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) conducted in 2005. What makes the suppression of the survey data particularly intriguing is that, overall, it conveys good news and projects a significant drop in child malnutrition rates in India over the past decade. Yet, the Economist magazine recently reported that the data was never made public though the final survey report was available in October 2014.

Image Courtesy: flickr.com

UNICEF survey finds drop in child malnutrition

The overall findings of the survey indicate a significant drop in child malnutrition rates in the country in the past decade.

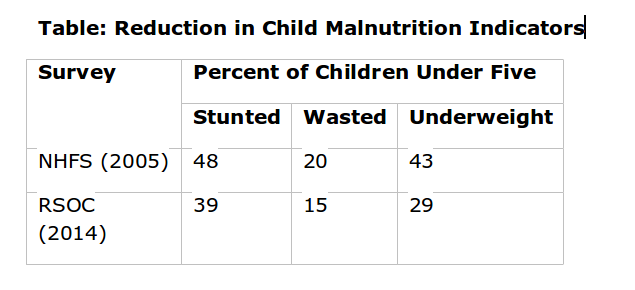

Table: Reduction in Child Malnutrition Indicators

Source: Data from NHFS, 2005, and RSOC as reported by the Economist

The drop in the rate of stunting, wasting and underweight of 9, 5 and 14 percent points is significantly more than the decrease between NHFS 2 in 1998-99 and NHFS in 2005-6. In the latter case rates of stunting and underweight decreased by 6 and 3 percent points respectively between 1998 and 2005, while the rate of wasting actually increased by 3 percent points in the same period. A caveat may be kept in mind, however, while comparing NHFS data and data from the RSOC. The two use different population sets and perhaps different methodologies and are not entirely comparable. Nevertheless the fairly large reduction indicated in the RSOC data over the past decade, in all probability, suggest a real reduction of malnutrition rates.

While all the three indicators – stunting, wasting and underweight – are measures of malnutrition in children, they provide different insights into the causes. The WHO suggests (Country Profile Indicators, Interpretation Guide, WHO) that the percentage of children with a low height for age (stunting) reflects the cumulative effects of under-nutrition and infections since and even before birth (thus including malnutrition in the mother). This measure can therefore be interpreted as an indication of poor environmental conditions or long-term restriction of a child’s growth potential. The percentage of children who have low weight for age (underweight) can reflect ‘wasting’ (i.e. low weight for height), indicating acute weight loss, ‘stunting’, or both. Thus, ‘underweight’ is a composite indicator of both stunting and wasting. Stunting is a better indicator of chronic under-nutrition and wasting of malnutrition due to recent causes, viz. recent food deprivation or serious illness.

India still one of the poorest performing countries

The RSOC report is indeed good news and we must have done some things right in the past decade for this to have happened. However a generous dose of caution is warranted before we start celebrating. Even if we accept the improved data, India still remains one of the poorest performing countries in the world as regards child nutrition. Further, poor performance in child nutrition is also an indication of broader systemic failures – including failure to provide adequate healthcare and other public health services, failure in provision of safe drinking water and sanitation facilities, failure of our agrarian policy, and failure to control and eradicate poverty. We have failed as a society if we are not able to feed our children and nothing else that we do can condone this neglect.

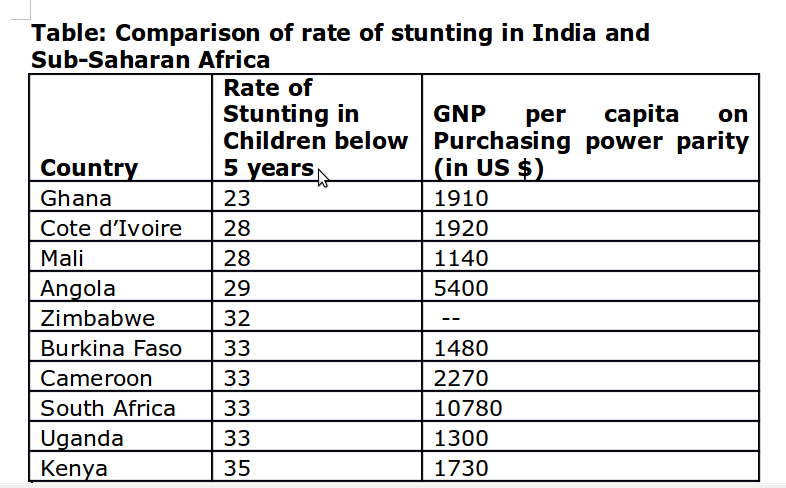

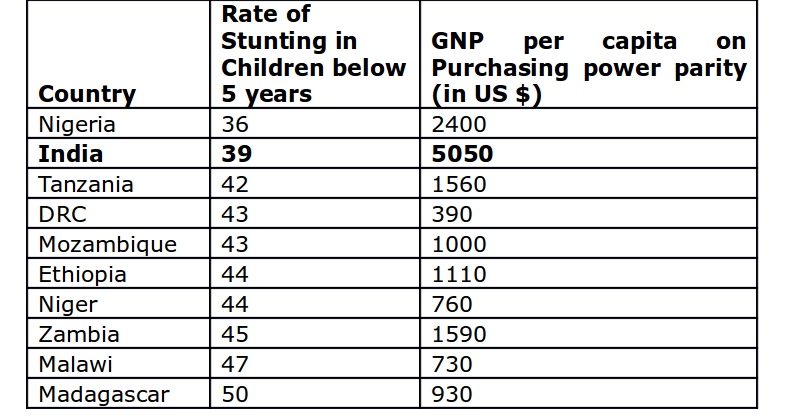

The continuing gravity of the situation can be understood if we compare the level of stunting among children in India (even after accepting the RSOC data) with levels reported in the poorest region of the world – Sub-Saharan Africa. If India were a nation in the Sub-Saharan region of Africa, the rate of stunting in India (39%) would be higher than the average for the region in 2013 (38%). The following Table provides a comparison of the rate of stunting in Indian children with those in all Sub-Saharan countries with a population of over 15 million.

Source: UNESCO, Education For All Global Monitoring Report, Sub-Saharan Africa: Overview, 2015

As we can see from the Table, India performs worse than 11 countries in the region and better than only 8 countries. This, in spite of India’s per capita wealth being 2-5 times that of most countries in the region (except South Africa and Angola). Clearly celebrations would be premature, especially for a country which claims to be one of the “emerging economies” of the world and projected to be (many would say through fraudulent data manipulation) the fastest growing economy in the world. Yet, the stark fact is, we are worse off as regards how well we are able to feed our children, than most of the poorest countries of the world.

Left influence and welfare programmes

But, as the RSOC data indicates, we seem to be on a course which could lead to significant improvements. It is important to try to make sense of how these improvements have been achieved. The past decade has been the period when the UPA Government was in power. During this period the government pursued neoliberal economic policies that promoted the interests of corporations and big business. Yet a mitigating factor was the introduction of some policies and programs that were directed at protecting people from the worst impacts of neoliberal reforms. This did not happen by accident or as a consequence of the large hearted munificence of the Congress led UPA Government. It happened as a result of continuous pressure exerted by the Left parties, who were able to wield some influence at the time of the UPA I government. Thus we saw the introduction of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) and the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). Some progress, though grossly inadequate, was made in guaranteeing food security through the public distribution scheme. Other schemes, directly addressing the nutrition needs of children, such as the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) and the Mid-Day meal scheme received some attention. Even after the exit of the Left parties during the UPA II government, the earlier momentum and the pressure of peoples’ movements from below kept most of these schemes going. None of these schemes and other social welfare programs was adequately resourced, but they did mitigate the impact of the neoliberal reforms in the past decade. It is entirely conceivable that one of the positive outcomes of these welfare programs (which the bourgeois press spares no effort to term as ‘populist’) is the drop in child malnutrition rates that we are seeing today.

Why suppress the survey results?

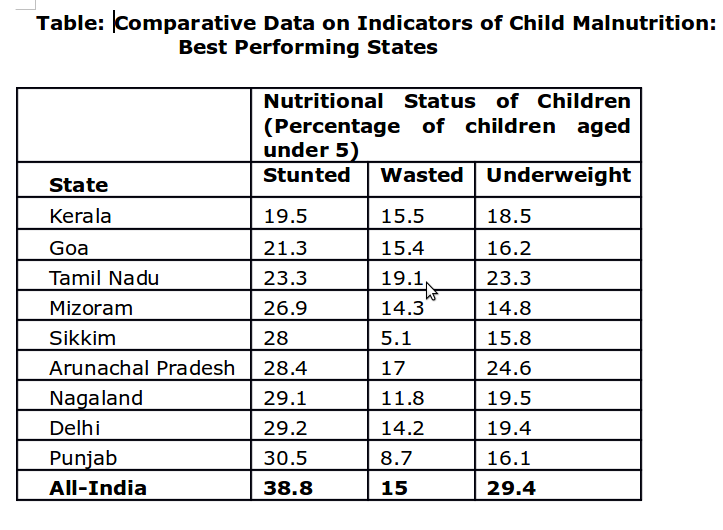

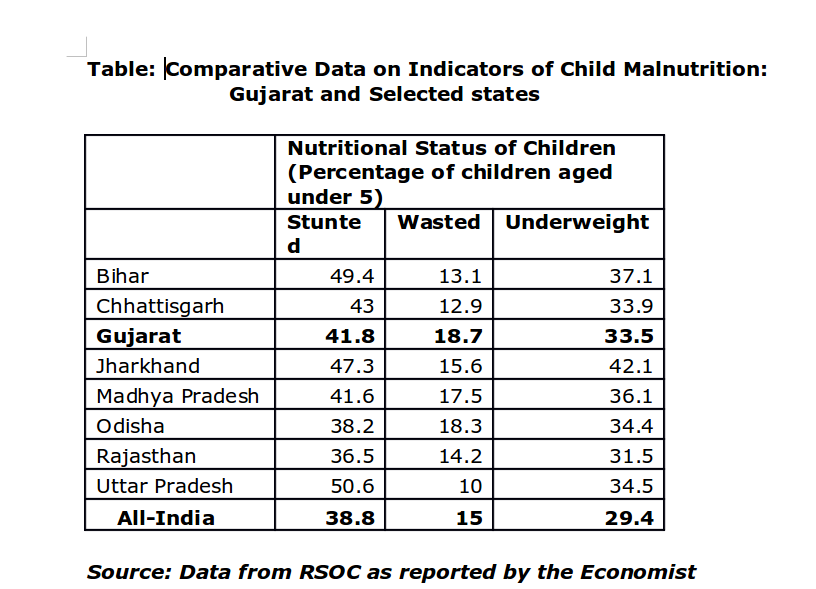

But the mystery still remains. One can understand (though not condone) the motivation of a government to suppress data that paints a negative picture of the country. But why would a government willfully suppress data that indicates some improvement in an area that has given cause to shame India over the past decades. If the data shows that we are starting to make a dent in child malnutrition, why keep it a secret? The explanation lies in the disaggregated state level data. If we examine the state level data, the findings in one state stand out. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s homes state, the state which he ruled with an iron fist for fourteen long years, is seen to perform worse than the national average in all the measures of child malnutrition. Not just that – Gujarat’s performance is at par (or worse in some cases) with the traditionally socio-economically backward states. The Table below provides a comparison.

Table: Comparative Data on Indicators of Child Malnutrition:

Best Performing States

Table: Comparative Data on Indicators of Child Malnutrition:

Gujarat and Selected states

Gujarat‘s performance (or more appropriately, lack of performance) is particularly striking as it is one of the wealthiest states in India in terms of state per capita GNP. As we see in the Table, Gujarat performs worse than Rajasthan in all 3 of the indicators, worse than MP and Odisha in 2 of them, and worse than Bihar, Jharkhand and UP in 1 of them. It is the worst performer among all states as regards the percent of ‘wasted’ children.

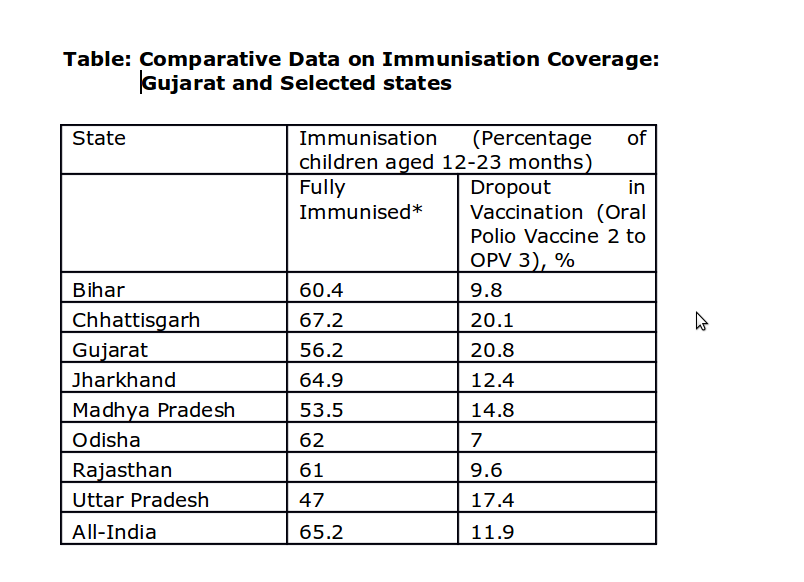

The survey data also includes information about public health programmes. The Table below provides comparative data about immunization. We can see that immunization coverage in Gujarat is worse than all other states except MP and UP. Further, it has the highest rate of dropouts in vaccination coverage.

Source: Data from NHFS, 2005, and RSOC as reported by the Economist

The cat is truly out of the bag now! Gujarat is the BJP’s and Narendra Modi’s poster boy of neoliberal reforms. Gujarat has been the BJP’s laboratory and the ‘Gujarat model of development’ was what the BJP has promised it shall bestow on the entire country. The Gujarat model of development is the most aggressive form of neoliberal polices that this country has known, combined with Sectarian policies that seek to further ghettoize and pauperise the already marginalised sections of society. The UNICEF survey data is but a small window to the consequences of BJP rule under Narendra Modi in the state.

Attempt to suppress evidence questioning neoliberal reforms

The Government’s compulsions probably do not stop at the need felt to shield Gujarat from uncomfortable questions. As we discuss earlier, the findings of the UNICEF survey also merit a close look at the kind of programs that could have contributed to an improvement in child nutrition. The problem is that it is precisely these policies that the BJP government has systematically targeted in the past one year. The recent Union budget has seen savage cuts in all programs designed to promote social protection and welfare. The BJP’s spin doctors are clearly uncomfortable with any evidence that might force a rethink on the aggressive pursuance of neoliberal reforms.

Unfortunately for the BJP and the NDA government, the key findings of the UNICEF survey are already available in public domain. The government has belatedly acknowledged that the UNICEF survey report does exist. It has gone on to justify the suppression of the report with the plea that there are methodological problems with the state level data. The government has even announced the setting up of a committee to examine methodological issues related to the survey. Clearly the government is clutching at straws while trying to defend the indefensible.