Global Capital, Digital Monopolies and New Forms of Enclosure

16/06/2019

THE beginning of the digital monopoly age, the age in which the digital monopolies start emerging and the neoliberal economic model has been roughly coterminous. Both come of age in the 90s. While the neoliberal economic model seems to be in a crisis, the digital monopolies show no sign of flagging. On the contrary, along with the continued expansion of older players, we are witnessing the rise of many new ones. It is clear that unlike the post 2008 crisis of the neoliberal model, the digital monopolies are not only not running out of steam, but also invading more and more areas of production, distribution and circulation of material goods. And as long as the technological changes that are driving the digital monopolies continue, the digital monopolies will either expand or give rise to new ones.

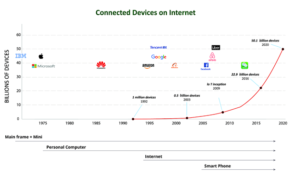

The chart above shows the impact of these technological changes: the new digital monopolies have overtaken the older oil, automobile and financial monopolies in just two decades. What is striking about this change is the pace at which this has happened. While the US companies are the world’s biggest digital monopolies today, the Chinese companies – Baidu, Ali Baba, Tencents, Huawei – are not very far behind.

The two major technology drivers behind this expansion of the digital monopolies have been the internet, which resulted in a huge increase in the connectivity of devices, and the other, the increase in computational speeds of the devices. Both these – the growth of connectivity and the increase of computational speeds – show no sign of flagging. Earlier, the connected devices were only main frames and mini computers, later, personal computers. Today smart phones, and with the Internet of Things (IoT) smart devices, are the bulk of devices connected to the internet. Both computational speeds and the rise of connectivity can be described in what are called power laws: computational speeds double roughly every 18 months, and connectivity doubles at a slightly slower rate.

Most people, including us in the Left, have attempted to explain the rise of digital monopolies in terms of data as the new oil paradigm. This focusses on the meteoric rise of Google and Facebook, and the use of personal data to fuel their rise. However, the rise of social media giants based on collecting peoples’ personal data does not explain the continued expansion of older companies such as Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon, or the rise of newer monopolies such as Uber and Airbnb. Clearly, there is more to the digital story than simply monetising personal data.

A different way of looking at digital monopolies would be to see them as operating on different forms of enclosures. The first set of companies – Microsoft and Apple – that emerged in the late 70s and became big in the 80s are still among the top ten companies today. They were based on intellectual property – Microsoft of software and Apple of hardware. The next set comprises social media platforms such as Google and Facebook, which have enclosed user data to create new monopolies. Their business model is based on advertising, selling their users to the advertisers. The latest monopolies to emerge are platforms monopolies in what is called the “sharing economy”. Of course this term – the sharing economy – hides the true nature of monopolies such as Uber that are enclosing “independent contractors” including their assets and converting them into new bonded labour.

An early forerunner of these is Amazon, which built a platform on which others could trade as a marketplace, with, of course, the platform taking the biggest cut. Though all of these – from Google to Uber – are based on platforms, their business models or mode of exploitation are quite different.

The charts here show the rise of connectivity and the various technological changes that have taken place. Before the rise of the internet, we had the main frame computers and the personal computers (PCs). IBM, the big player in main frames, believed that hardware had value and software was simply to be bundled with the hardware but by itself was not a commodity. The PCs created a market for software itself to be a commodity. Microsoft became the key player in this market, with DOS, later Windows, as the monopoly supplier of the operating system of the PCs. With this monopoly, they also built a software monopoly over products that ran on their operating system: word processing, spreadsheets, databases, etc.

The smart phone is the latest device that has changed how we connect to the internet. Google’s Android has the dominant market share, with Apple’s iOS a distant second.

Both these monopolies – of IBM over main frames, and Microsoft’s over software for PCs – depended on what the bourgeoisie call intellectual property. Intellectual property – copyright over proprietary software, hardware and design patents, underpin the monopoly of Microsoft or Apple. It is still the old fashioned monopoly that, for example, a pharmaceutical company or Disney exercises. This is what the commons movement has termed as the enclosure of the “intangible commons of the mind”; or theft of human knowledge from the commons converting it to private property.

Since then, with TRIPs/WTO agreements, the intellectual property regime has only strengthened. Apple and Google have sued their competitors for “theft” of intellectual property including what are called design patents.

Apple’s monopoly is based entirely on its ownership of intellectual property: it has the unique distinction of becoming the biggest manufacturer of smart phones and PCs without a single manufacturing plant. Foxconn, the company that manufactures the actual iPhone, receives only about $8.5 out of a total factory cost of $237.5 of the iPhone. More than 60 per cent of Apple’s revenue comes from its smart phone.

The communication monopolies of the 19th and 20th centuries, starting with the newspapers and later, radio and television, were all based on the broadcast model, and held their monopoly by owning the means of communications: printing presses, radio and television broadcasting equipment. The internet changed this mode of communications, it allowed a two-way communications making it possible for a large number of people to become consumers as well as content generators.

The problem with this expansion was that there is just too much of content on the web. This is where search engines came in. Initially, there were a large number of search engines, but Google won the race and emerged as the leading search engine. It is this dominance over the search engine market that allowed Google to create its other tools – Gmail, Google Docs – all of which are given “free” to the users. In lieu, Google accesses our personal information, and offers us to advertisers as commodity or what Dallas Smythe calls as audience commodity. These groups with similar interest are then sold as audience commodity to advertisers. This is targeted advertising and has a better conversion rate for the advertiser than advertising in the traditional media.

Facebook, the other major monopoly in the digital platform market, chose a different route. It created a space where people could put up content about themselves, and connect to their friends or relatives. Today, Facebook has 2.27 billion active users, making it the biggest social media network. This allows Facebook to create our profiles from who our friends are, what we like, or what we read or write. These profiles are used to generate audience profiles, which then can be sold to advertisers.

WeChat and Weibo are social media platforms in China, while Baidu is the Chinese search engine. These also have similar business models as the US based social media monopolies.

The chart of media ad spending shows how digital ad revenue is slated to overtake all other forms of ad revenue combined in the near future. Google and Facebook are increasingly taking over the advertising space from other media companies. The bulk of their revenues comes from selling targeted advertising, which has a higher rate of conversion than the ads that the traditional media companies carry. There is a bigger bang for the buck for advertisers using targeted advertising. While World Economic Forum extols the new, inexhaustible resource called data, economically creating audience demographies out of user data is a new form of enclosure. Earlier, personal data was not a commodity. It is enclosing this data – including the data of peoples’ social interactions, and processing it into audience demographies – that converts data into commodity. The enclosure of data commons has received much less attention than other forms of enclosures. Even those arguing against enclosure of user data tend to focus on how it can be monetised by users, rather than looking at it as a part of the commons that cannot be privatised either by companies or individuals.

Some mistake the advertising model as the only model for digital monopolies. As we have shown, Microsoft and Apple, digital monopolies based on intellectual property, continue to flourish and still figure in the top five global companies by market capitalisation.

Is there a third model that digital monopolies are adopting? For example, how do we look at Uber, Didi and Airbnb? Or the new food apps? Evgeny Morozev shows\ how the new platform monopolies that are now being created, use the help of venture/finance capital, the same ones that helped Google, Amazon and Facebook build their monopolies. Their business model helps these platforms to enclose the informal sphere of the economy. Uber and Airbnb convert individual vehicle and house owners to what they believe as independent contractors, but in reality glorified serfs! The sharing economy is the enclosure of personal property by digital monopolies and creating a new form of casual labour.

Amazon occupies a special place in this scheme. It started as a combination of digital equivalent of brick and mortar shopping chains/supermarkets. Unlike the traditional chains such as Walmart, it not only holds inventories in its warehouses, but also sells goods that it does not store. The inventory of such goods is held by either the producers or the distributors. Alibaba operates on a very similar model. It is possible to think of these monopolies as creating platforms that enclose shops owners and distributors warehouses; or as double-sided monopolies, as monopolies to their suppliers and a monopoly to their buyers, similar to Walmart. The economies of scale ensure that Amazon or Alibaba can make monopoly profits on both sides, the way Walmart did or still does.

It will be wrong to think that the growth of digital monopolies will taper off as the existing areas of their operation get saturated. This view misses out the fact that digital monopolies are now branching out into newer areas. Will the existing car manufacturers then become the Foxconns of the automobile industry as Google maps and autonomous vehicle software take over the car market? Will most factories shut down to make way for new ones with 3-D printing and flexible manufacturing? Will it create new monopolies over knowledge and design that will replace older monopolies based on manufacturing infrastructure?

As long as internet connectivity and processor speeds increase, the expansion of the digital monopolies will continue, with newer and newer areas of the economy coming under their control and disrupting existing business. The future of capital lies in the ability of capital to finance new digital monopolies. It is the relationship between finance capital and the new digital monopolies that we need to examine. The knowledge economy, social media, sharing economy – all these are different faces of contemporary capitalism. This is the task before us today: understand digital monopolies so that we can fight them better.